It’s Monday morning. The release went out on Friday. The “Done” box is ticked in Jira. The deployment pipeline is all green. Your dashboards show a neat row of passing checks. On paper, this thing is live and healthy.

Then you open Slack.

Support is dealing with a spike in “something’s not right” tickets.

SLOs are wobbling just enough to make SRE nervous, but not enough to trigger a clear incident.

Product is asking, “Do we know if this actually moved the needle on anything?”

The team insists, “But we shipped it. It was done.”

And technically, they’re right. You signed off on the Definition of Done. You followed it. You checked every box.

The problem is what those boxes represent.

Your Definition of Done is sitting somewhere in Jira or Confluence as a generic checklist: tests written, code reviewed, deployed to production, docs updated. It exists, but:

- It’s buried where nobody looks once the ticket is marked “Done.”

- It’s task-based, not outcome-based. It says what you’ll do, not what will be different.

- It’s invisible to product, operations, and support – the very people who live with the consequences.

So you keep hitting the same pattern: features that are “done” from the team’s perspective, but ambiguous, brittle, or underwhelming for the business. No shared picture. No shared risk boundaries. No shared proof that this was worth building in the first place.

That’s what this article is about: changing that conversation.

Instead of yet another abstract checklist, you’ll turn “Done” into a small, visual contract the whole cross-functional group can understand at a glance.

In other words, you won’t just define “Done” – you will draw it.

This article is for engineering leaders in agile and product engineering teams who want to improve their Definition of Done. And in it, you’ll get a 5-layer sketch, a 20-minute ritual, and a one-page canvas you can roll out with your team this sprint.

TL;DR

- Most “Definitions of Done” are grey checklists: they track activity (tests, reviews, deploys) but say nothing about value, risk, or proof in production.

- A simple 5-layer sketch (Outcome, Functionality, NFRs, Constraints & Risks, Proof) turns “Done” into a visual contract the whole cross-functional group can align on in minutes.

- A 20-minute DoD ritual slotted into existing ceremonies (sprint planning, design reviews, release checks) is enough to sketch this for your riskiest work.

- A one-page DoD canvas in Jira/Linear/Notion keeps that sketch alive as the single source of truth while you design, build, ship, and operate.

- You don’t need a rollout program: run a 30-day experiment where each team applies this to the riskiest ticket in their sprint; if it doesn’t reduce surprises and rework, kill it.

Table of Contents

Why “Done” Is Broken in Most Teams

If your Monday morning scene feels familiar, it’s rarely because your teams are lazy or careless. It’s because the system they’re working in has fuzzy finish lines.

Parkinson’s Law says that work expands to fill the time and space available. In tech teams, “Definition of Done” often expands to fill whatever the current ticket, sprint, or release needs it to be. The finish line moves. The meaning of “Done” changes from team to team, from project to project, and sometimes from one Slack thread to the next.

When “Done” is vague, teams optimize for the only concrete things: tasks completed, tickets closed, deployments shipped. Not value. Not risk. Not proof.

And this is how it looks in practice.

The Grey Checklist

In most organizations, the Definition of Done lives as a generic checklist:

- Tests pass

- Code reviewed

- Deployed to production

- Docs updated

It’s not wrong. All of those things are useful. But as a Definition of Done, it fails in three important ways.

First, there is no explicit user or business outcome.

The checklist tells you what the team will do, not what will be different when they’ve done it. As a rule of thumb, there’s no mention of activation, retention, MTTR, support volume, conversion, or any other leading indicator. “Done” means “we did the work,” not “the world changed in a quantifying way.”

Second, there are no risk boundaries.

Nothing in that list says what’s unacceptable. No line says, “We are not willing to degrade this SLO,” or, “We will not roll this out without a rollback plan,” or, “We won’t ship if cost per transaction exceeds X.” The team is aiming for “works” in a very narrow sense – compile-time and happy-path tests – instead of explicitly stating what must not break.

Third, there is no proof in production.

You can pass all the tests in the world and still have:

- Silent failures in the wild.

- Performance regressions at scale.

- Dark corners where edge cases live.

The checklist doesn’t tell you where you’ll see the impact in dashboards, logs, or user behavior. It doesn’t define what success or failure looks like once real users are touching it.

The result is a grey Definition of Done: it technically exists, but it doesn’t create a sharp boundary between “not yet” and “we’re confident enough to live with this in production.”

No Shared Picture Across Functions

The second problem is that every function carries a different picture of “Done” in their head.

For Product, “Done” often means:

The feature flag is live and customers can see the thing we promised.

For Engineering, “Done” often means:

The code is merged, tests are green, and the deployment pipeline says success.

For Ops/SRE, “Done” often means:

SLOs are stable, alerts are quiet, and there’s a clear runbook and rollback plan.

None of these perspectives is wrong. The issue is that they rarely get drawn together into a single artifact before work starts. So what happens?

“Done” becomes negotiable.

- Product pushes to keep a risky change live because a customer demo is coming up.

- SRE wants to roll back because error rates are creeping up in a way that doesn’t show in the feature’s happy-path tests.

- Engineering is stuck in the middle: “We’ve done what was asked. What exactly are we arguing about?”

Without a shared picture, “Done” is only really defined after something goes wrong:

- After a customer complains.

- After an incident review.

- After a missed target.

That’s an expensive time to discover that you were all imagining different end states.

How This Shows Up for Leaders

From a distance, all of this just looks like “normal delivery risk.” Close up, it’s a pattern of leadership headaches that repeat across every level of the org.

For CTOs and VPs of Engineering, it becomes hard to know which initiatives are actually safe to ship. You hear green status reports, see completed tickets, and get reassurances that “the DoD is met,” but you still feel uneasy signing off. You know from experience that “Done” usually means “Done-ish, unless…” and those “…unless” clauses keep turning into incidents and rework.

For Heads of Engineering and Engineering Managers, it shows up in retros full of the exact phrases:

- “We thought this was done…”

- “We didn’t realize that would be an issue until it hit production.”

- “We assumed someone else was thinking about that.”

The team does the work. The checklist is followed. Yet you keep uncovering blind spots that were never written down, let alone visualized or agreed.

For Tech Leads, it’s pull requests and design docs that stall out.

Reviewers ask, “What exactly is the behavior here?” or “What are the performance expectations?” or “What’s our rollback plan?” – and the answers live in someone’s head, or a chat thread, or a meeting nobody documented. The result is friction, slow reviews, and a lot of last-minute “can we just tweak this one thing?” changes.

Another slogan about ownership or quality solves none of this. You don’t need more abstract principles; you already have plenty of those.

What’s missing is a simple, visible framework that forces teams to agree – in concrete terms – on value, risk, and proof before they start writing code. A small playbook that turns “Done” from a grey checklist into a shared picture everyone can point at and say:

“That. That’s what we’re committing to.”

The 5-Layer Definition of Done (Sketch)

So what replaces the grey checklist?

A 5-layer sketch that forces the team to answer five simple questions before they write a line of code:

- What outcome are we aiming for? (green)

- What behavior are we changing? (blue)

- What quality bar must we meet? (purple)

- What risks and constraints are we accepting? (red)

- How will we prove it in the real world? (black)

You don’t need a new tool for this. One A4/Letter page, a whiteboard, or a FigJam/Miro frame is enough. The important thing is that it’s visual, fast, and shared.

Let’s walk through each layer.

Layer 1: Outcome (Green): Value & Metric

What it is

The green layer is a single sentence that describes the change you expect to see in the world, plus how you’ll know it happened:

“By <date>, we will see <user/business change> as measured by <leading metric>.”

For example:

- “By April 30, we will see more successful mobile top-ups as measured by a +10% lift in top-up completion rate.”

- “By June 15, we will see faster incident resolution as measured by a −20% reduction in MTTR.”

- “By July 31, we will see fewer billing complaints as measured by a −30% drop in billing-related support tickets.”

Why leaders should care

This is where you prevent “task-complete, impact-unknown.”

A clear outcome sentence:

- Anchors the work in value, not activity.

- Gives you a leading metric you can check within 2–4 weeks of release.

- Makes it much easier to talk about trade-offs: “If we don’t think this will move the metric, why are we doing it?”

Without this line, everything else can look good while the business quietly gets nothing.

Questions to ask

When the team is stuck, ask:

- “What will be observably different for users/customers?”

- “Which metric should move within 2–4 weeks of release?”

- “If this went perfectly, what graph would we screenshot for the board?”

Example

“By April 30, we will see fewer abandoned sign-ups as measured by a +10% increase in users who complete onboarding.”

That’s enough. Green layer done.

Layer 2: Functionality (Blue): Before → Change → After

What it is

The blue layer is a 3-frame storyboard of the behavior you’re changing:

- Before – how things work today, or the current pain.

- Change – what the system will now do differently.

- After – the new normal once the change is in place.

You draw this with simple boxes and arrows. No one is being assessed on artistic skill here, so don’t worry if it doesn’t look like Norman Foster’s work.

Why leaders should care

This is where you flush out hidden assumptions:

- Product, engineering, and ops often have slightly different mental models of what “the feature” actually does.

- A simple storyboard forces the conversation: “Wait, when exactly do we call the fraud check?” or “Who sees this notification and when?”

That’s cheap to discover on a whiteboard. It’s expensive to find out via an incident report.

The good analogy here is an old-school marketing agency. In the old days, before the onset of Gen AI capable of rendering entire movies, creative directors, designers, and copywriters would sketch a storyboard of a commercial to visualize the sequence of frames (steps).

Questions to ask

To keep it concrete, use action verbs. For each frame, ask:

- “In this step, what does the system do? Detect, decide, notify, deny, approve…?”

- “Who or what is acting? User, service, cron job, third-party API?”

- “What happens next if this step succeeds or fails?”

Example

Let’s say you’re adding an extra fraud check to online payments.

- Before:

“User submits card details → payment service attempts charge → if approved, we mark order as paid.” - Change:

“User submits card details → fraud service scores transaction →- If the score is low, the payment service attempts a charge.

- If the score is high, we hold the order and notify the review team.”

- After:

“Suspicious transactions are held for review instead of auto-approved, and clean transactions still flow through without extra friction.”

Three frames, some arrows, a couple of labels. Blue layer done.

Layer 3: Quality & NFRs (Purple)

What it is

The purple layer is a short list of non-functional requirements and cost guardrails that must hold for this to be considered “Done”:

- Latency

- Reliability

- Privacy/security

- Accessibility

- Cost ceiling

For example:

- “p95 latency for checkout API <200 ms.”

- “Error rate for fraud check integration <0.1%.”

- “No new PII stored outside our approved locations.”

- “Page remains usable on mobile and screen readers.”

- “Average extra fraud check cost <$0.04 per transaction.”

Why leaders should care

This is where you head off “works on my laptop” incidents.

Most post-mortems contain some version of:

- “We didn’t consider the performance impact at peak.”

- “We assumed the third-party API would be reliable.”

- “We forgot about the cost implications at scale.”

By making NFRs explicit:

- You align changes with existing SLOs/SLAs rather than undermining them by accident.

- You bring FinOps thinking into the conversation early: “Are we OK paying for this extra call on every request?”

- You give QA and SRE a clear target for their tests and dashboards.

Questions to ask:

- “Where could this hurt us at scale: latency, errors, cost, or security?”

- “What minimum bar do we need so this doesn’t trigger a ‘how did this get through?’ moment later?”

- “Which SLOs must not degrade because of this change?”

Example

For the fraud-check feature:

- “Added fraud check must not add more than 50 ms p95 latency to checkout.”

- “New integration error rate must stay below 0.1%.”

- “No card data or PII stored outside our existing PCI-compliant systems.”

- “Additional fraud check cost <$0.04 per transaction on average.”

That’s the purple layer.

Layer 4: Constraints & Risks (Red)

What it is

The red layer is about guardrails and anti-goals: what you are explicitly not doing or willing to tolerate in this slice, plus how you’ll pull back if things go wrong.

It has two parts:

- Constraints/anti-goals: “We will not…”

- Rollback trigger: “If X happens Y times in Z minutes, we flip back/disable.”

Why leaders should care

This is the difference between “We’ll see how it goes” and “We know exactly when this is no longer acceptable.”

Being explicit about constraints:

- Keeps scope under control (“We are not redesigning the whole checkout right now”).

- Protects critical flows and SLOs when enthusiasm for the feature is high.

- Makes rollbacks a predefined decision, not a political argument in the middle of an incident.

Questions to ask:

- “What failure modes are we willing to accept during rollout? Which are non-negotiable?”

- “What’s explicitly out of scope for this release?”

- “What objective signal tells us we should roll back instead of just ‘monitoring’ longer?”

Example

Continuing the fraud-check feature:

- Constraints/anti-goals:

- “We will not change the existing payment provider in this slice.”

- “We will not introduce extra steps in the checkout UI for low-risk customers.”

- “We will not roll this to 100% of traffic before we’ve validated on 10%.”

- Rollback trigger:

- “If checkout failure rate exceeds +0.5 percentage points above baseline for more than 10 minutes, we immediately disable the new fraud check and revert to the previous flow.”

That’s the red layer. You now know what you refuse to trade away.

Layer 5: Proof & Acceptance (Black)

What it is

The black layer defines how you’ll prove the change behaves as expected in the real world, using a small set of acceptance checks and telemetry.

Typically:

- 3–5 Given/When/Then checks per frame (or per key scenario)

- For each, a note: “Verified in <dashboard/log/alert>.”

Why leaders should care

This is where QA, SRE, and product get on the same page about “What good looks like”:

- QA gets concrete scenarios to test.

- SRE gets clear signals for alerting and dashboards.

- Product gets a way to see if the intended user behavior actually shows up.

Without this layer, “Done” means “We clicked around in staging, and it seemed fine.”

Questions to ask:

- “What are the 3–5 most important scenarios we must see working?”

- “Where do we see them – which dashboard, log view, or report?”

- “What would we screenshot to claim, ‘Yes, this is working as intended’?”

Example

For the fraud-check feature, some black-layer checks might be:

- Given a low-risk transaction, when the user completes checkout, then the fraud service is called, and the payment is approved within our latency budget.

- Verified in: “Checkout performance dashboard” + “Fraud service call logs.”

- Given a high-risk transaction, when the user submits payment, then the order is held for review, and the review queue count increments.

- Verified in: “Fraud review queue dashboard.”

- Given normal traffic levels, when the feature flag is enabled for 10% of users, then the overall checkout success rate stays within ±0.2 percentage points of baseline.

- Verified in: “Checkout success rate dashboard.”

That’s enough to either give you confidence or quickly show you where to look if something’s off.

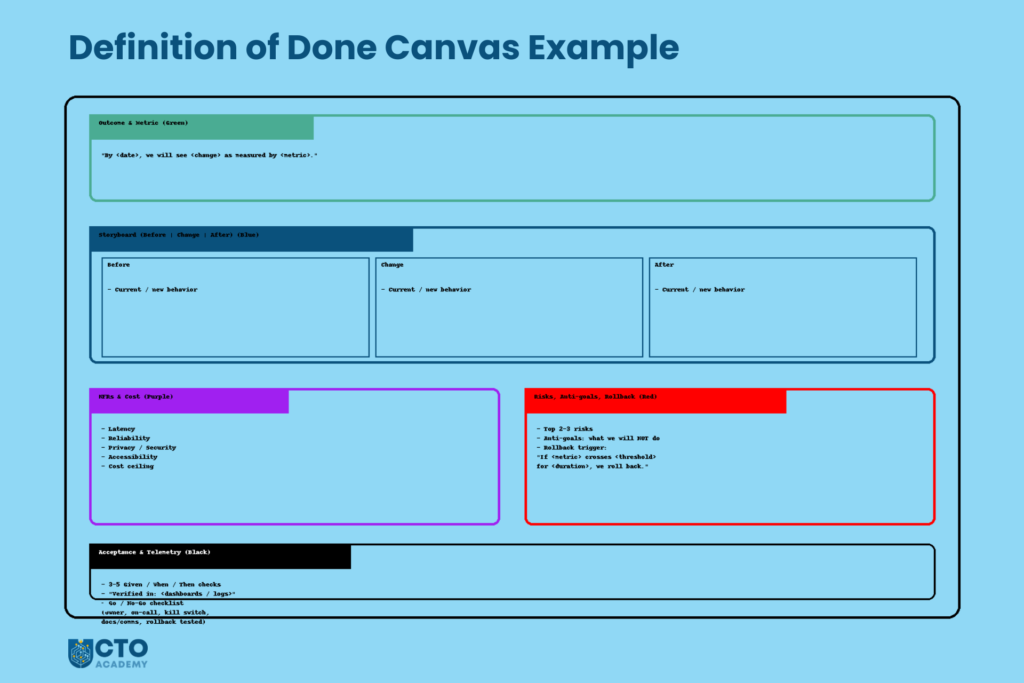

At the end of this 5-layer exercise, you have one page that looks roughly like this:

- At the very top, a green sentence stating the outcome and metric.

- Underneath, a blue 3-frame storyboard showing Before → Change → After.

- To one side, a short list of purple NFR bullets (latency, reliability, privacy, cost).

- Next to that, a red box containing constraints, anti-goals, and the rollback trigger.

- Along the bottom, black acceptance checks with notes on which dashboards/logs will prove each one.

It’s not a beautiful diagram because it doesn’t need to be. It’s a visual contract that everyone can point at and say, “This is what ‘Done’ means for this change.”

The 20-Minute DoD Ritual

The sketch only works if it’s something your teams can actually do in the flow of work – not a once-a-year workshop. Think of this as a 20-minute meeting pattern you can drop into your existing ceremonies: same people, same tools, different conversation.

The rule of thumb: run the ritual before you do anything that will be painful to unwind.

When to Run It

You don’t need a DoD sketch for every spelling fix. Use it where the risk is non-trivial and the blast radius is wide.

Good candidates:

- New external integrations

- Payment providers, CRMs, data vendors, auth providers, fraud services.

- Billing or pricing changes

- Anything that can affect revenue, invoices, tax, or customer trust.

- Core workflow changes

- Onboarding, checkout, booking, search, account recovery – the flows users touch every day.

- Incident-prone areas

- Parts of the system with a history of outages, performance regressions, or repeated near-misses.

In terms of where it fits, you don’t need a new meeting. You attach the ritual to moments that already exist:

- Sprint planning – for the riskiest item in the sprint backlog.

- Pre-implementation design review – when you walk through the proposed solution.

- Release readiness review – before you flip the flag or roll out to a bigger cohort.

The pattern is always the same: “This item is risky enough that we deserve 20 minutes to draw what ‘Done’ really means.”

Who’s in the Room

You want just enough people to get a complete picture, and no more.

Minimum cast:

- Product owner/PM – owns the outcome; keeps the value and metric honest.

- Tech lead – drives the sketch; owns the system behavior and trade-offs.

- 1–2 key engineers – the people most likely to implement the work.

Optional but powerful:

- QA – to think through edge cases and acceptance checks.

- SRE/Ops – to represent SLOs, alerts, and rollout risk.

- Support/Success – to bring in “how this will land with customers.”

You don’t need the whole team. You want decision-makers and implementers, not spectators.

The Minute-by-Minute Agenda

Here’s the ritual in a tight 20-minute box. Share this script with your tech leads; let them run it as-is.

0–3 minutes: Outcome sentence + metrics (green)

Agree on the one-line outcome and the leading metric. Get it written at the top of the page.

- PM proposes a draft: “By <date>, we will see <change> as measured by <metric>.”

- Group sanity-checks: Is this specific enough? Realistic within 2–4 weeks of release?

- Tech lead asks: “Are we all happy that if this happens, we call this a win?”

By minute 3, the green sentence is visible to everyone.

4–10 minutes: Co-sketch 3 frames (blue)

Draw the Before → Change → After storyboard in three boxes.

- Tech lead holds the pen (or cursor) and narrates: “Right now, the flow looks like this…”

- Others interrupt to clarify: “Actually, there’s another path here,” or “Users can also come in via this route.”

- Keep it rough. Boxes, arrows, stick figures – anything is fine as long as everyone understands it.

By minute 10, you should have a simple, accurate depiction of what will actually happen in the system.

11–14 minutes: Add NFRs & cost caps (purple)

Now you ask, “What could hurt us at scale?”

- Quickly list latency, reliability, privacy/security, accessibility, and cost constraints.

- SRE/QA chime in with SLOs and error budgets.

- Someone notes where these will be checked (e.g., which dashboards).

By minute 14, your purple bullets say, “We’re only happy if it behaves at least this well.”

15–18 minutes: Name top risks, anti-goals, rollback trigger (red)

You switch to “What we’re not doing and what we won’t tolerate.”

- Name 2–3 constraints or anti-goals: “We will not change X… we will not roll out to 100%… we will not break Y.”

- Define a clear rollback trigger: “If metric M crosses threshold T for more than N minutes, we revert.”

The test: Could someone in ops make a rollback call purely from what’s written in this red box?

By minute 18, you know the boundaries and the emergency stop button.

19–20 minutes: Acceptance checks + telemetry (black)

Finish with 3–5 checks that prove this behaves as expected.

- QA helps draft Given/When/Then scenarios.

- SRE/Eng map each one to a dashboard, log view, or report: “Verified in <place>.”

Then:

- Take a photo/screenshot of the whole sketch.

- Paste it into the ticket, PRD, or design doc as “DoD Sketch – v1”.

At minute 20, you’re done. People can stay and debate details if they want, but the core contract is captured.

Leaders Tips

A few small habits make the difference between a useful ritual and yet another bloated meeting.

- Protect the timebox.

The power of this pattern is that it’s quick. If it regularly drifts to 45 or 90 minutes, teams will stop volunteering risky work for it. Encourage leaders to be ruthless: when the timer hits 20, freeze the sketch and move on. - Make the tech lead the driver.

The tech lead owns the pen and the flow of the conversation. This keeps things grounded in concrete behavior rather than drifting into abstract strategy. PMs and others contribute, but there’s a single facilitator. - Let the PM guard the outcome.

While the tech lead draws, the PM keeps an eye on the green line at the top: “Are we still building something that would actually move this metric?” If the sketch and the outcome drift apart, they call it out. - Always end with an owner.

Before people leave the room, ask: “Who is the owner of this change, and who will update the ticket/doc with this sketch?” Name a person, not a team. Their job is to make sure the DoD sketch doesn’t stay on a whiteboard that gets wiped.

Run this ritual a few times, and it will start to feel like muscle memory: 20 minutes of drawing, a clear definition of “Done”, and far fewer surprises when you ship.

The One-Page “Definition of Done” Canvas

The sketch on the whiteboard is great in the moment. The problem is what happens next:

- Someone wipes the board.

- Someone else tries to reconstruct it from memory.

- Six weeks later, nobody can remember what you actually agreed.

You need something just as simple, but slightly more structured, that can live inside your standard tools.

That’s the job of the one-page DoD Canvas – a small template you can reuse in Jira, Linear, Confluence, Notion, or whatever you use to manage work.

Think of it as the “snapshot” of that 20-minute ritual.

Let’s break it down.

Sections of the Canvas

You want the canvas to fit on a single screen or piece of paper. No scrolling through multiple pages. No fancy formatting. Just clear, labelled sections that mirror the five layers.

1. Outcome & Metric (green)

At the top, 1–2 lines:

- The outcome sentence: “By <date>, we will see <user/business change> as measured by <leading metric>.”

- Optional: a baseline + target: “Current checkout success rate: 78%. Target after change: 86%.”

This keeps everything anchored in value.

2. Storyboard (Before | Change | After) (blue)

Next, a simple three-column section. Let’s reiterate what we already have:

- Before – one or two bullets describing the current behavior or pain.

- Change – what the system will now do differently.

- After – the new normal, once the change is rolled out.

You can:

- Paste a photo of the whiteboard sketch, or

- Drop in a tiny diagram from FigJam/Miro, or

- Even use three small code/sequence snippets if your audience is very technical.

The point is that someone can glance at this and instantly see what’s actually changing.

3. NFRs & Cost ceiling (purple)

Then, a short bulleted list of non-functional requirements and guardrails:

- Latency: “p95 < 200 ms on API X.”

- Reliability: “Error rate < 0.1% for Y.”

- Privacy/security: “No new PII outside approved store.”

- Accessibility: “New flow passes our WCAG AA checks.”

- Cost ceiling: “Extra cost per transaction < $0.04 on average.”

This is usually 3–7 bullets. That’s enough to express the bar, but not enough to become a spec of its own.

4. Risks, Anti-goals, Rollback trigger (red)

A clearly labelled “Risk & Constraints” box:

- Risks – the top 2–3 things you’re worried about.

- Anti-goals – what you explicitly will not do in this slice (“We are not redesigning the entire onboarding flow”).

- Rollback trigger – one line like: “If checkout failure rate exceeds baseline by +0.5 ppts for more than 10 minutes, we disable the new fraud check feature flag.”

This gives anyone looking at the canvas a quick answer to: “What are we afraid of, and when do we bail out?”

5. Acceptance & Telemetry (black)

Here, you list the concrete checks that prove the thing works:

- 3–5 Given/When/Then bullets, e.g.,:

- “Given a low-risk transaction, when the user completes checkout, then the fraud check runs and the order is marked paid within our latency budget.”

- “Given a high-risk transaction, when the user submits payment, then the order is held for review and appears in the review queue.”

- For each, add a line: “Verified in: <dashboards/logs>.”

Examples:

- “Verified in: Checkout Performance dashboard (Grafana).”

- “Verified in: Fraud Review Queue dashboard.”

- “Verified in: Support ticket tag report (Zendesk).”

Now you’ve wired your definition of “Done” directly to the places where you’ll see real-world proof.

6. Go/No-Go checklist

At the bottom, a tiny checklist that can be ticked before rollout:

- Owner confirmed: named individual accountable.

- On-call aware: the on-call engineer is aware of the change.

- Kill switch/flag in place (and tested).

- Docs updated: runbooks, internal docs, customer-facing if relevant.

- Comms ready: support, sales, CS know what’s coming.

- Migration/rollback tested, not just written down.

This is the safety net. It makes the difference between “We think this is fine,” and “We’ve actually prepared to live with this in production.”

How to Embed It in Your Tooling

The canvas only works if it lives where your teams already are. You don’t want a separate system for this.

In Jira/Linear

- Create a description template or snippet with the canvas sections as headings:

- Outcome & Metric

- Storyboard (Before | Change | After)

- NFRs & Cost

- Risks, Anti-goals, Rollback

- Acceptance & Telemetry

- Go/No-Go checklist

- During the 20-minute ritual:

- Someone fills in the text live, and

- You attach a photo of the whiteboard or FigJam sketch directly to the ticket.

This makes the ticket the single source of truth: anyone reviewing or implementing can see exactly what “Done” means for this change.

In Confluence/Notion

- Create a reusable page template called “DoD Canvas.”

- Use the same structure as above, with headings and bullet placeholders.

- Link each canvas page to:

- The corresponding Jira/Linear ticket, and

- Any design docs or RFCs.

Over time, this gives you a library of DoD canvases for past releases. It’s handy when you’re doing incident reviews or planning follow-up work.

In practice

To make this real, keep the commitment small and sharp:

“For the next 30 days, every risky ticket gets a DoD Canvas before work starts.”

Define “risky” however you like – money, security, core flows, new dependencies – and let teams nominate candidates.

After 30 days:

- Look at a handful of canvases.

- Ask teams: “Did this actually help? Where did it save us pain? What can we simplify?”

- Keep the bits that work, trim the rest.

The goal is not to add ceremony. The goal is to make “Done” visible, specific, and shareable, all done in one page that your teams can create in minutes and rely on for months.

How Different Leaders Use This

The mechanics are the same everywhere: a 5-layer sketch, a 20-minute ritual, a one-page canvas.

How you use those tools changes with your role.

You don’t need a full-scale transformation program. You need a handful of small, repeatable moves that fit the level you operate at.

CTO/VP Engineering

At this level, you’re not running the ritual yourself. Your leverage comes from making it a regular part of how big decisions are made.

You can use DoD sketches as:

- Gates for high-risk bets.

For any initiative with serious downside risk – new product lines, big architecture shifts, pricing changes, strategic integrations – make the ask simple: “Before we commit, I want to see the Definition of Done sketched out on one page.”

If the team can’t produce that sketch, it’s a signal that the work isn’t ready yet. - Artefacts in portfolio/steering reviews.

Instead of scrolling through status slides, review a small set of DoD canvases for your top initiatives:- What outcomes are they aiming for?

- What risks are they accepting?

- What rollback triggers have they defined?

It’s a fast way to see whether your org is taking risks consciously or by accident.

- Coaching tool for leaders.

When a VP, Head of Engineering, or EM brings you a problem, ask: “Show me the DoD sketch for this initiative.”

If there isn’t one, you’ve found a coaching opportunity. Not “Why didn’t you think of this?” but “Let’s run the ritual on the riskiest part and see what falls out.”

Your job isn’t to police every Definition of Done. It’s to make clear that serious bets deserve a serious definition, and you expect to see it drawn, not just written.

Head of Engineering/Director

You sit where strategy meets day-to-day delivery. You’re close enough to see the work, far enough to influence multiple teams.

You can make DoD canvases part of how your area runs.

- Require a DoD canvas for epics above a certain threshold.

For example:- “Any epic that touches money, data loss risk, or SLOs must have a DoD canvas before we start implementation.”“Any change with more than two teams involved needs a shared DoD sketch.”

- Enforce canvases for user-facing changes in critical flows.

Payments, auth, onboarding, search, account management – they’re always high stakes. Standardize your expectation: “If users can’t complete [X] because of this change, we’re in trouble. That means this flow always gets a DoD canvas.” - Use them in release and cross-team design reviews.

Rather than diving straight into low-level design, start reviews with the canvas:- “Walk me through the Before → Change → After.”“What are the purple NFRs you’ve committed to?”“What’s your rollback trigger?”

Your role is to ensure that every significant change in your domain has a clear, shared, and portable definition of success and safety.

Engineering Manager/Tech Lead

This is where the ritual really lives. You’re close enough to the work to run it, and senior enough to make it stick.

Use the 20-minute DoD ritual in your existing ceremonies:

- Sprint planning

When you look at the next sprint:- Ask, “What’s the riskiest ticket or epic here?”

- Run the DoD ritual for that one item.

- Capture the canvas directly in the ticket.

- Story kickoffs

Before people disappear into implementation, gather the small group, share the ticket, and:- Spend 20 minutes sketching the 5 layers. Make sure everyone sees the same picture of “Done.”

- Incident follow-ups (“new DoD”)

After an incident, when you’re planning the fix:- Run the DoD ritual as part of the post-mortem or follow-up work.

- Treat the new DoD canvas as a “guardrail contract” for that area: “This is how we stop this from happening again.”

For EMs and tech leads, the DoD sketch is a practical leadership tool: fewer misaligned expectations, better planning conversations, and clearer guardrails when you’re under pressure.

Senior ICs/Staff Engineers

You might not own the ceremonies, but you carry a lot of influence. This is a great place to lead from the middle.

- Propose a sketch for one scary ticket.

When you see something risky coming up – a migration, a new dependency, a complex refactor – you can say: “This feels risky enough that we should draw a Definition of Done. Can we spend 15–20 minutes sketching it?” Then volunteer to facilitate. Run the ritual once, keep it light, and let people feel the difference. - Teach juniors to think in outcomes, risks, and proof.

Use the 5 layers as a coaching framework:- Ask them to write the green outcome before they start designing. Ask them to draw a simple blue storyboard of Before → Change → After. Ask them what’s on the purple NFR list, and how they’ll know in production (black proof).

You don’t need formal authority to use this. You just need to be the person who says, “Let’s draw it,” when everyone else is about to jump straight into code.

Used this way, the DoD sketch stops being “yet another template” and becomes a shared language across levels:

- The CTO uses it to challenge big bets.

- Directors use it to structure reviews and control risk.

- EMs and tech leads use it to run better planning and follow-through.

- Senior ICs use it to elevate the conversation.

Same five colors. Same 20-minute pattern. Very different leverage, depending on where you sit.

Common Anti-Patterns and How to Fix Them

Even with a good framework, teams will find creative ways to bend it back into old habits.

The point isn’t to shame anyone. It’s to recognize the patterns quickly and have minor, practical corrections you can apply this week – not after a six-month transformation.

Grey-Scale Definition of Done

Symptom

Your Definition of Done is a tidy list of tasks:

- Tests written

- Code reviewed

- Deployed to production

- Docs updated

…but there’s no value and no proof. No outcome, no metric, no way to tell if this was worth doing beyond “we shipped it.”

You still get:

- Features that land with a shrug.

- Tickets marked “Done” while nothing noticeable has changed for users.

- Difficult conversations about priorities because everything looks equally “important.”

Fix this week

Don’t rip up the checklist. Color it in.

For the next sprint, pick one substantial ticket or epic and do the following:

- Add one green outcome line at the top of the ticket: “By <date>, we will see <user/business change> as measured by <leading metric>.”

- Add three black acceptance checks at the bottom, each with “Verified in: <dashboards/logs>”.

Example:

- Green: “By March 31, we will see fewer abandoned sign-ups as measured by a +10% increase in completed onboarding.”

- Black:

- “Given a new user, when they complete the form, then they land on the dashboard page. Verified in: onboarding funnel dashboard.”

- “Given a new user on mobile, when they submit the form, then the submission success rate stays within 0.2 ppts of desktop. Verified in: mobile vs desktop conversion dashboard.”

- “Given normal traffic, when we roll this to 100%, then overall sign-up conversion remains ≥ baseline. Verified in: global sign-up conversion dashboard.”

You’ve just converted a grey checklist into a mini contract on value and proof, with almost no extra ceremony.

Endless Scope Creep

Symptom

You start drawing the storyboard and realize:

- The Before picture doesn’t fit in one box.

- The Change block has five parallel flows and three side quests.

- The After picture includes “and in the next phase we’ll also…”

Your DoD becomes a dumping ground for every related idea. The box can’t fit the work. “Done” quietly expands to mean “everything we’ve ever wanted to do in this area.”

You still get:

- Slippery deadlines.

- Bloated “MVPs” that are anything but.

- Teams that are always 80% through something important.

Fix this week

Turn the storyboard into a scope constraint.

For the next piece of work you plan:

- Draw the Before → Change → After storyboard.

- Apply this rule: “If the story’s storyboard doesn’t fit cleanly into three frames, the work is too big. We split it.”

Practically:

- If “Change” contains multiple unrelated behaviors, ask:

- “Which behavior gives us the most learning or has the greatest impact the earliest?”

- Make that an epic with its own DoD sketch.

- If “After” includes “and we’ll also refactor X and upgrade Y and tidy Z,” move the refactors into separate follow-up tickets with their own (lighter) DoD.

You’re not killing ambition. You’re forcing the team to define a slice that can genuinely be “Done” – with clear outcomes, risks, and proof – instead of living in endless almost-done.

“Works on My Laptop” DoD

Symptom

The team is happy because:

- Unit tests pass.

- CI is green.

- The feature works as expected in the staging environment.

But the DoD sketch has no NFRs, no cost ceiling, and no telemetry. Nobody has written down:

- How fast does it need to be under load

- What error rate is acceptable

- What will this do to your cloud bill

- Which dashboards will show if it’s healthy

You still get:

- Performance surprises at peak.

- Quiet degradations that nobody notices until customers complain.

- “How did this get through?” moments in incident reviews.

Fix for this week

Patch the purple and black layers onto what you already have.

For the next release:

- Add 2–3 purple NFR bullets to the existing definition of done:

- One about latency or responsiveness

- One about the error rate or reliability

- One about either security/privacy or cost

- For each of those, specify where you’ll see it:

- “Verified in: <SLO dashboard> / <APM view> / <FinOps report>.”

Example:

- “p95 latency for Checkout API remains < 200 ms. Verified in: API latency dashboard.”

- “Error rate for payment provider integration < 0.1%. Verified in: integration error dashboard.”

- “Extra cost per transaction < $0.04 on average. Verified in: monthly cost report for payment services.”

You don’t need to design the perfect SLO stack in a week. You just need to make sure “Done” includes a minimum quality bar and a way to see it.

No Rollback Plan

Symptom

The Definition of Done talks about:

- Deliverables

- Tests

- Documentation

It says nothing about what happens if this causes pain in production.

Rollback is something you only discuss:

- In the middle of an incident.

- With a lot of adrenaline.

- While people are arguing over whether it’s “really that bad.”

You still get:

- Hesitation when you should be reverting.

- Long incidents because nobody is sure how or when to pull back.

- Political discussions about “optics” instead of technical calls about risk.

Fix this week

Make rollback part of “Done,” not an optional extra.

For every DoD sketch you create over the next sprint, add two things to the red layer:

- A rollback mechanism

- “Feature flag named <X> that can be turned off without redeploying.”

- “Blue/green deployment with the previous version kept warm for 24 hours.”

- “Reversible migration script with tested down path.”

- A rollback trigger in one line: “If <metric> crosses <threshold> for <duration>, we roll back using <mechanism>.”

Example:

- “If error rate on checkout exceeds 2x baseline for more than 10 minutes, we disable the ‘NewCheckoutFlow’ feature flag and revert to the previous flow.”

Write it down. Point at it during release: “We’re all agreeing this is the line.”

You’ve just moved rollback from “something we’ll think about if needed” to a predefined, agreed part of Done.

You don’t need to fix every anti-pattern at once. Pick one – grey-scale DoD, scope creep, “works on my laptop,” or missing rollback – and run the “Fix this week” play for a couple of sprints.

The goal is progress, not purity: fewer surprises, clearer boundaries, and a Definition of Done that actually earns the name.

A 30-Day Experiment (Make It a Habit)

You don’t need a big rollout plan to get value from this. You need a small, controlled experiment that proves (or disproves) the value in your own context.

Here’s a 30-day path that fits around the expected delivery.

Week 1: One High-Risk Ticket

Pick one scary piece of work. That’s it.

- New external integration

- Billing/pricing change

- Core flow tweak (checkout, onboarding, auth)

- Anything that’s bitten you before

Then:

- Run the full 20-minute DoD ritual

- Outcome & metric (green)

- Storyboard (blue)

- NFRs & cost (purple)

- Risks & rollback (red)

- Acceptance & telemetry (black)

- Paste the sketch into Jira/Linear

- Either as a photo of the whiteboard, or

- Filled out as a one-page DoD canvas in the ticket description

- Ship as normal

- Don’t change the rest of your process yet.

- Just treat this one ticket as the “DoD experiment” and observe how it feels.

The bar for success in Week 1 is simple: Did this make conversations more straightforward and decisions easier?

Week 2–3: Riskiest Ticket per Team

If Week 1 felt useful, you scale the experiment slightly.

- Identify 2–3 teams or streams of work.

- For each, agree: “Every sprint, we’ll run a DoD sketch for the riskiest ticket.”

Concretely:

- In sprint planning:

- Ask, “What’s the riskiest thing in this sprint?”

- Block 20 minutes to run the ritual for that one item.

- Attach the DoD canvas to its ticket.

- During the sprint:

- Refer back to the canvas in standups, reviews, and when questions arise.

- Notice what changes:

- Do reviews go faster?

- Are fewer assumptions popping up late?

- Do conversations with Product/Ops feel less fuzzy?

You’re not trying to cover every ticket. You’re building a habit around risk: scary work comes with a clear, visual Definition of Done.

Week 4: Review and Decide

At the end of roughly 30 days, pause and inspect.

Bring together a small group of EMs, tech leads, and PMs who’ve used the sketch, and ask three sets of questions.

1. What actually changed?

- How many “we thought this was done…” surprises did we have on work with a DoD sketch versus work without one?

- Did any incidents or near-misses come from items that had a DoD canvas? If yes, did the canvas help you respond faster?

- Did we see fewer last-minute arguments about scope, risk, or rollback on those items?

You’re looking for directional signals, not perfect metrics.

2. What did people like or hate?

Ask the people who were in the room:

- Developers:

- “Did the canvas help you understand what was being asked?”

- “Did it make implementation decisions easier or harder?”

- PMs:

- “Did the green outcome + metrics make prioritization clearer?”

- “Did the storyboard surface gaps earlier?”

- QA/SRE:

- “Did the purple NFRs and black proof sections make it easier to know what to test/monitor?”

And don’t be afraid of the negatives:

- “This part felt repetitive.”

- “We got stuck on the outcome sentence.”

- “Five acceptance checks were overkill for small changes.”

Those complaints tell you where to trim.

3. What do we keep, tweak, or drop?

Run a short retro and decide:

- Keep:

- Which parts of the ritual clearly pulled their weight?

- Maybe the green outcome line and red rollback trigger are non-negotiable.

- Tweak:

- Do you need fewer acceptance checks?

- Should the storyboard be optional for minimal backend changes?

- Do you want a lighter version of the canvas for low- to medium-risk items?

- Drop:

- Any steps that consistently add time but do not bring clarity to your context.

End Week 4 with one explicit decision:

“For the next quarter, our standard is: <your simplified, battle-tested DoD pattern>.”

If the experiment showed no value, you also have a clear decision:

“We tried this for 30 days. It didn’t move the needle. We’re not adopting it.”

Either way, you’ve treated Definition of Done like any other product: prototype, test, refine – instead of rolling out a grand policy and hoping for the best.

FAQs & Objections

We already wrote acceptance criteria. Why add a sketch?

Acceptance criteria are great, but they’re usually text-only and story-sized. The sketch adds three things you rarely get from bullet points:

A shared picture of Before → Change → After.

A clear link to outcomes, NFRs, and rollback.

A single page that Product, Eng, Ops, and Support can all understand in seconds.

You don’t have to replace acceptance criteria. Start by adding a DoD sketch only to one high-risk item per sprint. If it doesn’t make conversations more straightforward, kill it.

Won’t this slow us down?

For low-risk changes, you won’t use it at all. For high-risk changes, you’re already paying the cost – just later and more painfully:

In incidents

In rework

In endless back-and-forth about “what we meant.”

This is 20 minutes you spend up front to avoid hours or days of confusion and cleanup later.

If you’re worried, set a strict constraint:

“We’ll only use this for one risky ticket per team for two sprints. If it doesn’t save us time or pain, we stop.”

Is this only for product teams, or also for infra/platform?

It works just as well for infra, platform, and internal tooling – sometimes better:

Outcome: “Reduce MTTR by 20% for service X.”

Storyboard: Before → new debugging tool/dashboard → After.

NFRs: Impact on latency, resource usage, cost.

Risks: Blast radius if the change goes wrong.

Proof: SLO dashboards, incident stats.

Anywhere you’re changing behavior in a system that real people rely on – including engineers – you can benefit from a clear Definition of Done.

Where do we store these sketches?

Wherever the work already lives:

Jira/Linear – in the ticket description + attached photo of the whiteboard.

Confluence/Notion – one “DoD Canvas” page per epic, linked from tickets.

The rule of thumb:

“If someone is touching this work, they should be one click away from the DoD canvas.”

Don’t invent a new system. Attach the canvas to the existing source of truth for the work.

What if we can’t agree on the outcome or metric?

That’s a feature, not a bug.

If you can’t agree on: What “better” looks like or how you’d notice it within 2–4 weeks, then you probably aren’t ready to build yet. The DoD sketch has done its job by revealing that.

In practice:

Timebox the argument to a few minutes.

If you’re stuck, pick a “good enough” metric and mark it as a learning bet:

“We’re not sure this is the perfect metric, but we’ll try it for this slice and adjust.”

You can refine the metric next time. You can’t unship a feature that never had a clear purpose.

Do we really need all five layers every time?

No. The five layers are the full version. Your implementation can have a “light” mode.

For example:

A tiny cosmetic change on a non-critical page:

Green outcome + 1–2 black checks might be enough.

Backend improvement with no user-facing change:

Green outcome, purple NFRs, and black proof may be all you need.

A simple rule:

“The higher the risk and blast radius, the more of the five layers we use.”

Start with the full five for a couple of risky items, then deliberately decide what’s safe to trim in your context.

How do we prevent this from turning into bureaucracy?

By treating it like everything else you build: experiment, measure, adjust.

Keep it timeboxed (20 minutes).

Keep it targeted (risky work only).

Run a retro after 30 days:

What helped?

What was noise?

What can we simplify or remove?

If your teams feel the DoD canvas helps them avoid surprises and make better calls, keep it. If they feel like it’s just bureaucracy, strip it back or drop it.

The goal isn’t to comply with a template. The goal is to ship fewer nasty surprises and have a Definition of Done that actually means something.

Conclusion & Next Steps

Most of the pain you feel around delivery doesn’t come from bad intent or lousy code. It comes from unfinished conversations.

Drawing the Definition of Done forces those conversations to happen early, when misunderstandings are 10–100× cheaper to fix. Instead of discovering misalignment in an incident review, you discover it on a whiteboard with a pen in your hand.

A one-page DoD sketch gives you:

- A shared outcome everyone can point to.

- A clear picture of what’s changing and why.

- Explicit quality bars, risk boundaries, and rollback triggers.

- Concrete proof in production that this was worth shipping.

You don’t need a grand rollout to start. You just need one move:

- Pick the riskiest ticket in your next sprint and run the 20-minute ritual.

Capture the five layers, paste the sketch into Jira/Linear, and ship as you usually would. Then see how it changes the conversations around that work.

If it helps:

- Share a photo or your DoD canvas template with your leadership team.

Use it in one portfolio review, one release review, and one incident follow-up. Let people experience how quickly it cuts through fuzziness.

And if you want to go further, this approach pairs nicely with how you manage time, scope, and capacity overall. A clear Definition of Done is even more powerful when combined with visible constraints – the same ideas behind Parkinson’s Law and limiting the work you let expand to fill your calendar and your roadmap.

Start small—one risky ticket, one sketch, one sprint. See what surfaces when you stop just defining “Done” and start drawing it.